What animal lives more than 250 years but never eats a thing? If you guessed the deep-sea tubeworm Escarpia laminata, you would be correct—and also probably a deep-sea biologist!

Escarpia laminata lives near deep-sea cold seeps, places where methane (natural gas) and toxic hydrogen sulfide gas leak from the sea floor. Although it is among the longest living animals known, E. laminata never has to eat. In fact, it does not even have a mouth! Instead, its body is filled with a special type of bacteria that absorbs hydrogen sulfide from seawater and uses it to power chemosynthesis, a process similar to photosynthesis except it is fueled by chemical energy (sulfide oxidation) rather than sunlight.

Deep-sea tubeworms can grow in large colonies, as seen in this image taken by a research submarine during one of Dr. Fisher’s expeditions (Photo credit: Fisher Deep-Sea Lab).

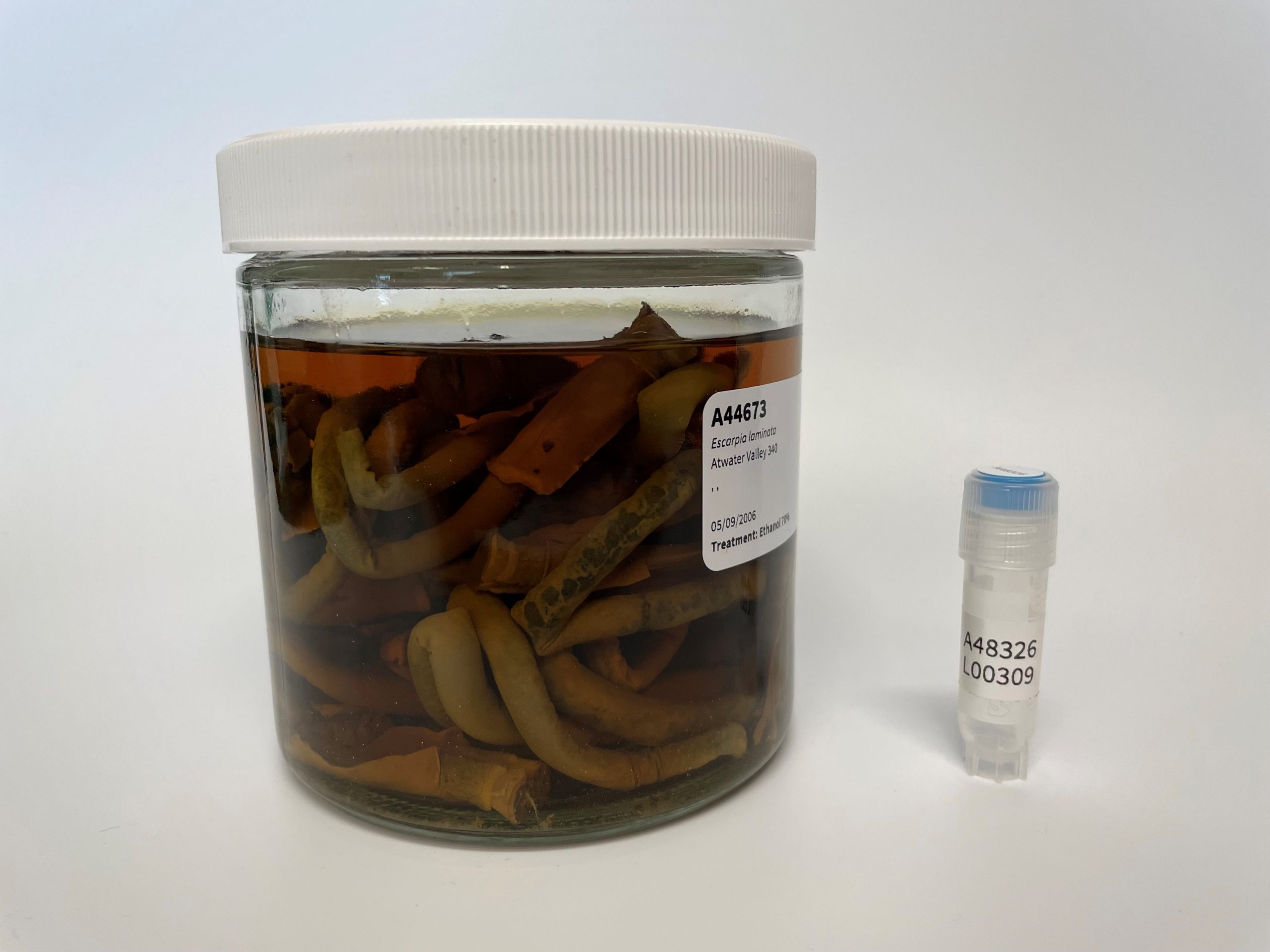

Escarpia laminata is also one of over 1,000 new samples donated to OGL by retired researcher Dr. Charles Fisher, and it was accessioned into the OGL collection by OGL’s newest undergraduate research co-op, Lee Fenuccio (a co-author of this newsletter). During his career, Dr. Fisher was a leading pioneer in studying deep sea organisms. Lee, on the other hand, is an aspiring researcher just getting started in their career. Together, their efforts are creating a new resource that that deep-sea biologists, and scientists of all stripes, will be able to study and explore.

An example of an E. laminata voucher specimen (left) and tissue sample (right) from Dr. Charles Fisher that have been accessioned into the OGL collection. The voucher specimen contains several tubeworms preserved in ethanol, and the tissue sample is stored at –80° Celsius. (Photo credit: Lee Fenuccio, OGL)

Interested in helping OGL acquire more specimens for research? Donate here.