We are all familiar with the genetic code—the simple set of three-letter words that translate the As, Ts, Cs, and Gs of DNA into the diverse and complex forms we know as animal life. But, if every cell in an animal has the same DNA, how does one cell know to become a brain cell rather than a heart cell? And how do these cells know to assemble into a fin, wing, or finger?

It turns out that eukaryotic organisms—animals, plants, and fungi—have a second kind of code that adds chemical marks to specific locations in the DNA without altering the underlying DNA sequence. The most common process, called DNA methylation, adds marks to the DNA that instruct genes when to turn on or off. This allows different cells to have different fates. It also allows organisms to respond to changes in their environments, ramping up or turning down genes that help an organism respond to challenges like starvation or heat stress.

“DNA methylation provides the cells with epigenetic memory, ensuring that a liver cell always remains a liver cell and a heart cell always remains a heart cell—even though all cells in our body are equipped with the same genes.”

—Dr. Christoph Bock

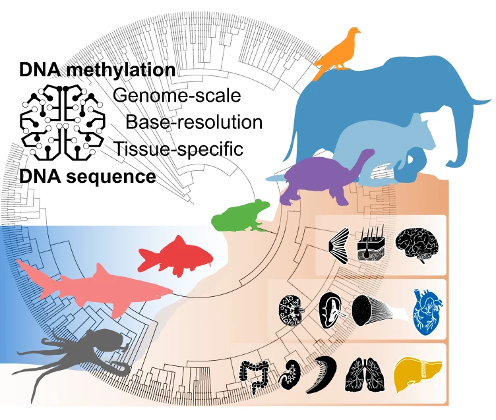

Figure 1. Visual summary of the research. Figure credit: Klughammer et. al 2023.

This week, researchers led by Dr. Christoph Bock from the CeMM Research Center for Molecular Medicine of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna published an unprecedented study of DNA methylation in 580 species from across the animal kingdom. The researchers found that although different animal groups show different DNA methylation patterns, animals share certain elements of a common code as old as the animal kingdom itself. For example, the DNA methylation patterns in starfishes and sharks are similar to those seen in orangutans or humans.

Understanding patterns of DNA methylation is crucial to grasping the evolution of complex life, and may provide insights into aging and human disease. For example, there seems to be a correlation between high methylation rates and low cancer rates in large, long-lived birds such as eagles and penguins. This finding may help to explain and treat diseases relating to aging and cancer in humans.

To make this research possible, Ocean Genome Legacy (OGL) scientists helped to select and provide more than 600 specimens that represent different tissues of a broad array of fishes and marine invertebrate species—the modern descendants of the species that formed the base of the animal tree of life.

This high-impact research would have been extremely difficult without the help of a biorepository like OGL, and is a great example of what can be accomplished when scientists, including the many depositors to OGL, share the specimens that they collect around the world!

Want to help OGL enable more exciting work like this? Support OGL here.